+

+

May 22, 2020

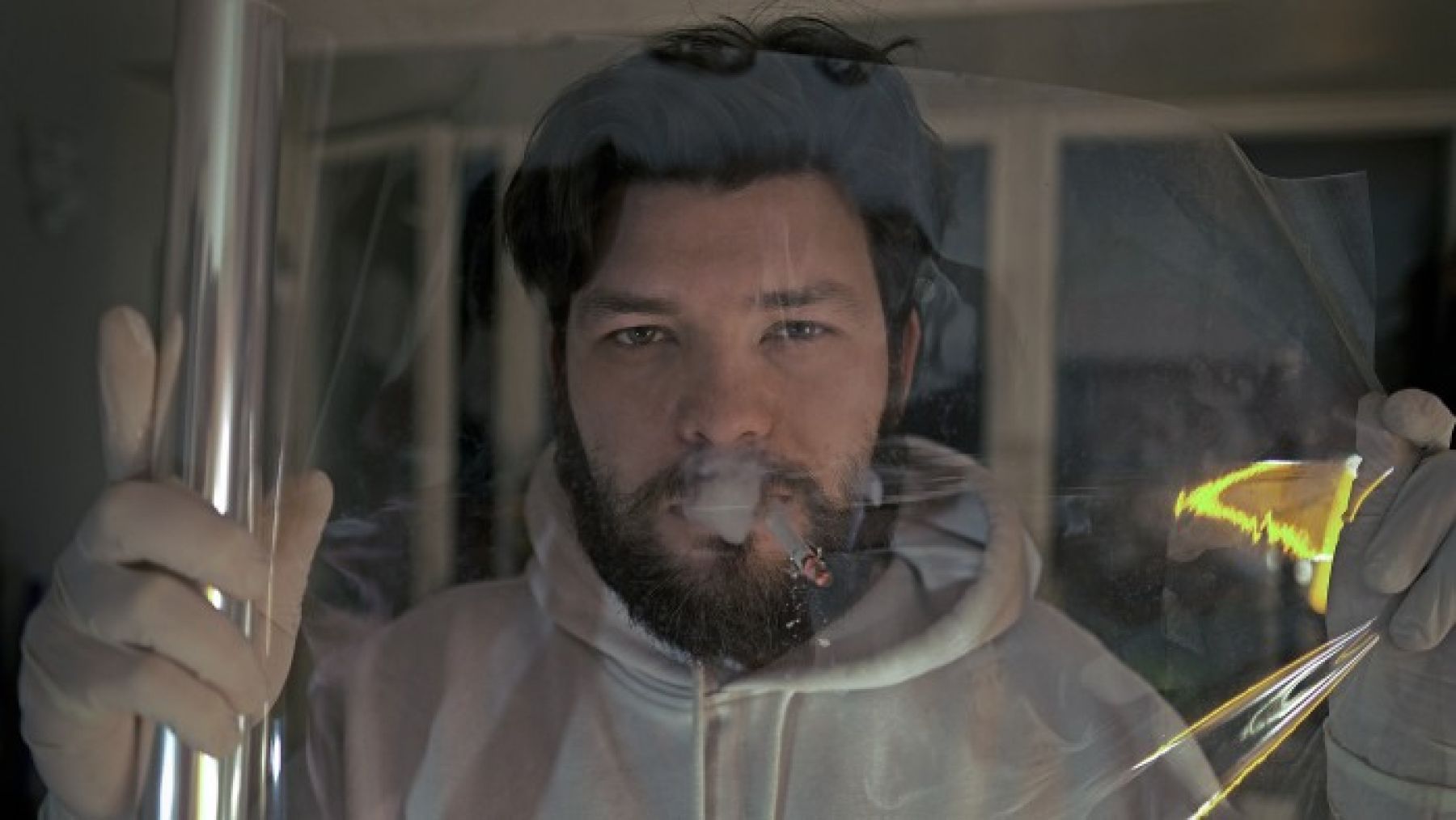

Ironic interview with Kirill Basalaev about his artistic expression, his perception of quarantine reality and a new series of works.

TOMSK, Siberia

Has your native city, the Siberian Tomsk, influenced your art? I am referring to its uneven urban landscape, ravines and beams

I am 32 years old, I have been living outside of Tomsk for the last 7 years. I do come back quite regularly though, for a couple of days, mostly to visit my parents. I always felt uncomfortable in Tomsk, it is too small for me, if I stay there for longer than usual I go crazy. We used to joke with my friends that Tomsk was an island from the TV series “Lost”. It is like a swamp to me but with a positive connotation, of course. Many interesting people live in Tomsk, beautiful and smart people but it is absolutely not the place for me.

Regarding the influence, undeniably it exists. It is the city where I was born, and the native environment, as we well know, plays a vital part in a person’s life. It is in Tomsk that I became interested in art and, firstly, in photography. I was taking snapshots of a person or a place which I subsequently deconstructed in a way that would make the image harder to understand. Photography quite soon ceased to be a sufficient means of expression for me and I turned to books. I discovered Roland Barthes and through his works I learned about Ferdinand de Saussure, Jacques-Marie-Émile Lacan, Walter Benjamin and others. That was the turning point for me and I decided to make a move and begin my career as an artist. I entered the faculty of Art and Culture at The University of Tomsk but was expelled three years later… or left of my own accord, I don’t quite remember now but it was a rather comic situation.

Tells us about your works. How did you come to abstraction? How much does the medium that you use influence your creative process?

My technique started to form in Moscow. The big city played a huge role in influencing my work. The metro, wide streets, skyscrapers, crowds and the fake feeling of freedom. The euphoria of relocation faded away quickly, I felt almost immediately how alienated and soulless the city really was. Back then I worked as a courier, I drove a lot delivering mostly iphones around Moscow and its suburbs. On my trips I would photograph fragments of walls with scratches and cracks, buildings in construction or already in ruin. During that period, the concept of my works crystallised: the urban landscape as a constant self-destructive structure where a human has to support life. So I started to interpret those photographs on canvases recreating those walls again as paintings using their natural medium - concrete, plaster and primer. I would use the paint that the city council services would normally use in their repair works: enamel paint, nitro synthetic enamel, water-based paint. The actual address on the real wall was used as the title of the painting. I did not think of those works in terms of abstraction, on the contrary they were quite defined “cityspaces” if you like.

IRONY

Is it true that your paintings are about the fast passage of time and the processes of destruction?

At the moment I am not so interested in discussions about the city, its fragile state and a human’s place in a megapolis as well as in their relationships. The process of creation and destruction is the object of my research, from my point of view the two processes are the same. If before I would say that the city opens up to the viewer with its rough parts, gets into a dialogue by exposing its cracks and scratches, now it is about the post ironic homage to my earlier works from 3-4 years ago. I am reusing my own experience, I am not rethinking anything, I am trying to downgrade all what has been created before. Bright colourful levels of plaster, cuts and abrasions are transformed into grotesque marks misleading the viewer from the main idea behind it. If before I was welcoming this dialogue, I am ignoring it consciously now. My works are ironic colourful abstractions, where the richness of texture, split pieces of paint and dissected levels is nothing else but the reminder of the end.

However, death in itself is of no interest to me, no more than life at least. When talking in the context of art we put these terms in brackets, and death becomes an artistic expression. I am more attracted to the process of dying, more precisely to the ways an object is losing its main features. The mass of colourful primer covered in paint is a meaningless depth captured by the frame of a painting. Fontana wanted to escape from the image, he wanted to create a new space within, while I am more concerned with the cut in the depth of the medium as opposed to the canvas. It is similar to emotionally-sick teenagers that harm themselves by performing small cuts on their bodies, say, on the inside part of a leg, in order to feel something new.

I think my works are graceful and beautiful in a way, they even fit interiors sometimes, it is also a part of that grotesque joke I talked about earlier. The “beauty” brushes off many questions and relaxes in a similar way as parodies on horror movies. My works are about me and for me to some extent. The painting becomes finished once it is hanging on an exhibition wall or being bought. This transition is also its death, it becomes the witness of itself from that moment on. I abrogate all responsibility when I reveal my paintings to the world, they cease to be mine.

QUARANTINE

How do you get inspired during quarantine?

March 15th was the day when I decided to take some time off: to stay at home and detox from social networks. I bought bear and bourbon whisky and planned to enjoy my own company for a while. When I became tired of being at home, it turned out that everything had been closed and everyone had also been staying at home. So I have been self-isolating for 2 months. Any live communication and visual variety are very important for me. Almost everything I go through finds its reflection in my works. By being locked down in my flat I have experienced all the stages of Kübler-Ross*.

Not so long ago I found myself in a strange state - unresponsive, nostalgic, empty. It was similar to a feeling of forgetting something very important that vanished and does not return back but only keeps the memory of that something being important, the void. I have united two English words “inside” and “silence” and gave them a name, I called this new state “insidelence”. This has become the theme for my new body of work. To sum up, it is a hard, scary and very interesting time at the moment. We are observing the last breaths and cries of the 20th century, it has been with us for over 20 years. However, its rules are no longer valid.

* Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (July 8, 1926 – August 24, 2004) was a Swiss-American psychiatrist, a pioneer in near-death studies that developed the concept of psychological help to terminally ill people. Her book “On Death and Dying” was published in 1969 where she summed up her experience and listed 5 stages of perception of death during terminal illnesses: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.